Market Segmentation Theory: Unveiling the Myths of Interests

Last update: 11 January 2023 at 03:37 pm

At its core, the market segmentation theory assumes that there is no correlation between short-term and long-term interest rates, and the interest rate for each different maturity segment is different from the other.

Introduced in 1957 by John Mathew Culbertson, an American economist, the theory works on the premise that each bond securities market segment is primarily composed of investors who have varied duration preferences.

Some prefer short-term, some long-term, and some opt for the intermediate. For instance, banks prefer short-term securities, while insurance institutions prefer investing for the longer term.

In fixed-income securities, borrowers and investors have their preferences for particular yields.

These varied preferences result in sharply segmented compartmentalized markets that have unique supply and demand dynamics.

Yield of a Debt Instrument and Its Maturity Period

The yield of a debt instrument refers to the rate of return you can expect to gain at the end of your tenure if you hold a debt instrument until its maturity.

There are different calculations for measuring yield, such as Bank Discount Yield (BDY), Holding Period Yield (HPY), Money Market Yield (MMY), Effective Annual Yield (EAY), etc.

While we do not need to go into the specificities of each of these calculations, we must understand that irrespective of the calculation we use, yields for one category of maturities cannot predict the yield for a different category of maturity.

We can draw a host of inferences from this understanding. To begin with, we should look at the overall market as a collection of potential buyer segments.

Each segment has its common set of needs and each of these segments responds to different marketing actions. Resultantly, there is no point in spending your marketing budget trying to reach all sorts of players in the market.

Some groups will buy your products and there will be some who won’t. Therefore, the most prudent strategy would be to decide your target groups and marketing your product only to that group.

4 Different Yield Curves: The Result of Market Segmentation

By now, it is evident that if you are the buyer of a debt instrument, such as a bond, for the short term, your characteristics as an investor and your investment goals would differ significantly from that of an investor who has put his/her money in a long-term bond.

Let us reconsider the previous example of banks and insurance companies.

Insurance firms tend to invest in long-term bonds because they want to maximize their income. On the other end, what drives the banks to go for short-term bonds is minimizing volatility and protecting their principal and liquidity.

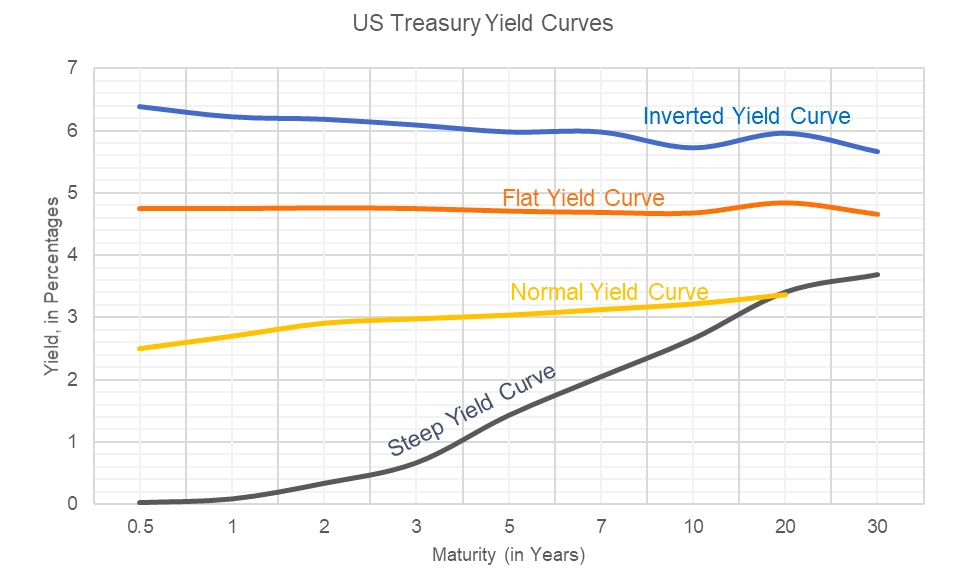

You can understand the distinct supply-demand characteristics of bond yields for different maturities, through yield curves. Yield curves for the US government’s Treasury debt are also reflective of the macro-economic condition of the country.

In a normal yield curve, you will find longer-term bonds having higher yields than shorter-term ones. It indicates the conditions of an expanding economy, where default risk increases with longer investment tenures.

An inverted yield curve implies a situation where shorter-term bonds have higher yields. Getting an inverted yield curve implies the imminence of a recession and is a sign of a worsening economy overall.

The flat yield curve is when short and long-term bond yields become identical. When you get a flat yield curve, you must take it for a sign of transition in the economy, either from a recession to an expansion or the other way round.

A steep yield curve normally signifies an increase in interest rates in the near future. It shows that the short-term yields are normal, but that the long-term yields are at a higher level.

Preferred Habitat Theory: A Variant of MST

The Preferred Habitat Theory proposes that bond investors have their set preferences for maturity lengths. They can only go beyond that preference and buy bonds of a different maturity length if risk premiums for other maturity ranges are available.

Another interpretation of this theory suggests that, provided everything else is equal, an investor would always prefer to hold shorter-term bonds in place of longer-term bonds.

The market always incentivizes higher-risk-taking capacity with higher rewards. Resultantly, the yields on longer-term bonds should be higher than shorter-term bonds.

Now, let us see this theory side by side with the market segmentation theory. The preferred habitat theory suggests that bond investors are concerned about both maturity and yield.

But, the market segmentation theory suggests that investors only care about yield. They will invest in bonds of any maturity as long as they get the percentage yield they want.

If we see both these theories together, we will reach a vital conclusion driving the nature of the constitution of bonds. If you want to sell longer-term bonds or bonds that have a maturity period beyond your target group’s preference, you would have to add a premium. Resultantly, longer-term bonds will always offer a higher yield than shorter-term ones.

Implications of MST: Seeing through the Investors’ Lens

The relevance or validity of a theory always depends on what it implies for the people on the ground. Here, those people are the investors.

To understand the pertinence of market segmentation in these days and times, we must comprehend how it translates into the practical world of finance.

Let us consider insurance companies as investors here. They operate in a market where the most crucial parameter defining their performance keeps fluctuating. It is the interest rate.

Insurance businesses sell a product that is usually for the long term, life insurance policies.

A life insurance policy may range in its maturity anywhere between 20 and 40 years. Selling an insurance product is, therefore, the seller exposing itself, the insurance company in this case, to long-term liability.

To offset this liability, the insurance company needs to invest in long-term assets. Here, those long-term assets are long-term bonds.

But why not invest in short-term bonds and keep rolling that over?

It is precisely where the market segmentation theory plays its hand. It says that in terms of bond maturity, each type of bond (short-term or long-term) is a separate segment in itself, implying that it can not be interchanged.

They are not related, and the supply-demand dynamics of a particular segment exclusively determine the fate or yield of that segment.

Essentially, it boils down to if, as an investor, you are seeking to offset long-term liabilities, you can not achieve that by investing in short-term bonds and rolling them over.

If we assess this inference based on our financial market experience, we will see that it holds ground. An insurance company will hardly agree to bear the brunt of falling interest rates during the rolling over of short-term bonds.

This concept of compartmentalized segments, each driven by their internal supply-demand dynamics, is something that was a major shift from the earlier concept of “The Term Structure of Interest Rates,” which saw maturity and bond yields as plottings on a continuous curve.

The Proliferation of Market Segmentation in Other Areas

If you expand market segmentation theory from its immediate realm composed of debt, maturity, and yield, you will see that any market can be seen as a composite of market segments, parts, or sub-parts.

You can segment the market in terms of its geography of sales, product categories involved, or even in terms of needs.

Although these are divisions or sub-divisions of the same market, they are distinct from one another.

If you know how to segment your market, you can market your product to only those groups you consider your potential buyers.

It helps save your marketing budget and optimize your ROI.

Successful segmentation of the market requires establishing the market and the sets of targeted consumers first. It is a process that involves paperwork, surveys, the right analysis of the demographic and economic factors, and also testing the waters by advertising about the launch of the product.

The next is where you map your marketing procedures with the segments they cater to. Here, an experienced marketer would also target the decision-making consumers.

The next step is where you compile the initial feedback and consumer suggestions and work on them.

The fourth stage is the final one where after the initial churning and realignments, the actual segments start taking shapes. Consumers with the same need and demand come together to form robust, compartmentalized segments like investors interested in the same type of yield do.